May 29th, 2009 by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento in

Trademark

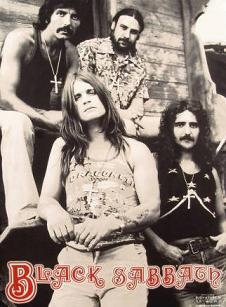

Ozzy Osbourne has filed a lawsuit with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office against his former Black Sabbath bandmate, Tony Iommi, claiming Iommi illegally assumed sole ownership of the Black Sabbath name. According to the New York Post, Osbourne’s suit seeks a 50 percent stake in the “Black Sabbath” trademark. Osbourne further contends that Osbourne is entitled to a portion of the profits Iommi has generated through use of the band name, and suggests it was Osbourne’s “signature lead vocals” that helped propel the band’s “extraordinary success.”

Rolling Stone has more here.

May 29th, 2009 by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento in

Art Law

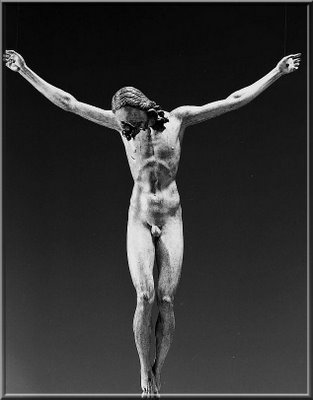

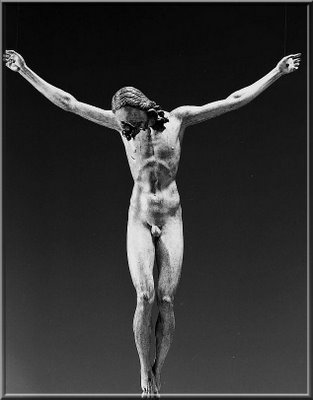

A few minutes after blogging about fakes, frauds, and forgeries, this story hot off the press. According to The Independent, Italians are squabbling over a presumed Michelangelo sculpture that may just be…a fake!

At the beginning of the year, the Italian government paid around €3.25m for a 16-inch-high wooden sculpture, Cristo Ritrovato, purchased by an Italian antiques dealer some 20 years ago on the hunch that it might be a youthful work by Michelangelo. The work is now the star attraction in a Naples exhibition devoted to early work by the artist – indeed, it is the exhibition’s poster boy, featuring on publicity for the show as a rediscovered work of genius. And that fact has irritated several academics and specialists who argue that it isn’t a Michelangelo at all, but actually a bit of political spin, intended to improve the government’s image with conservative voters.

For those interested in forgeries and art, Errol Morris is writing “Bamboozling Ourselves,” a seven-part installment based on two books, published last year, on the genius art forger Han van Meegeren. He writes:

Why do people believe in imaginary returns, frauds and fakes? Bernard Madoff, A.I.G. , W.M.D.’s … How did this happen? Do we believe things because it is in our self-interest? Or is it because we can be manipulated by others? And, if so, under what circumstances?

To be sure, the Van Meegeren story raises many, many questions. Among them: what makes a work of art great? Is it the signature of (or attribution to) an acknowledged master? Is it just a name? Or is it a name implying a provenance? With a photograph we may be interested in the photographer but also in what the photograph is of. With a painting this is often turned around, we may be interested in what the painting is of, but we are primarily interested in the question: who made it? Who held a brush to canvas and painted it? Whether it is the work of an acclaimed master like Vermeer or a duplicitous forger like Van Meegeren — we want to know more.

Part two, an interview with Edward Dolnick, the author of “The Forger’s Spell,” is also available now.

For those keeping tabs on the deaccessioning wars, a couple of notable stories have come out this week. For starters, it looks like New York’s Brodsky Bill–which will create rules for deaccessioning of items in a museum’scollection and regulate the use of funds from disposed items–is on the fast-track to being passed.

Pro-deaccessionists are hard to come by, but this week Guggenheim Director Richard Armstrong weighed in (at the heavyweight category), and basically opined that the deaccessioning self-righteousness of “provincial” art institutions will only hasten their death.

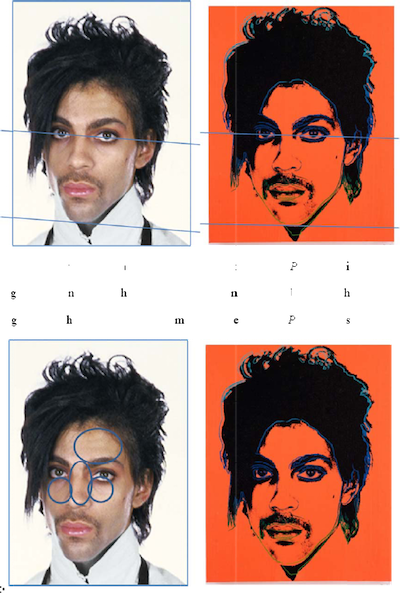

On May 26, a New York federal district court judge stated that an art collector’s lawsuit against the Andy Warhol Foundation and the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. Judge Laura Taylor Swain ruled that the suit by Joe Simon-Whelan, a London-based American filmmaker, could continue to the discovery phase on many of its claims.

According to the CBC:

In 1989, Simon-Whelan purchased for $195,000 US a silkscreen self-portrait print believed to have been created by the famed U.S. pop artist at his New York art factory in 1965. He contends that Warhol’s estate, several art dealers and some of the artist’s acquaintances declared the painting authentic. However, on the two occasions (in 2001 and 2003) when he submitted the work to the foundation and board, they denied authentication.

In 2007, Simon-Whelan filed a class-action lawsuit, accusing the two organizations as well as the exclusive sales agent for Warhol’s estate of engaging “in a conspiracy to restrain and monopolize trade in the market for Warhol works” for the past 20 years.

For other thoughts on this lawsuit, see Jeff Stark’s comments here, as well as other authentication cases.

May 20th, 2009 by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento in

Criminal

According to The Guardian, the disappearance of a Henry Moore sculpture worth £3m (approximately $4.6 million) has been solved by police. Police authorities believe that the Reclining Figure sculpture was melted down and sold for no more than £1,500 (approximately $2,300). The bronze sculpture was stolen from the 72-acre estate of the Henry Moore Foundation in Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, in December 2005.

May 18th, 2009 by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento in

Copyright

It is only a matter of time before an artist tackles this legal issue. According to today’s NY Times, the sale of virtual gifts, services and other fictitious commodities on the Internet has become a big business.

A “virtual good” is essentially a product or service that has perceived value to a user online but no tangible value in the outside world. It is as varied as imaginary flowers planted on a friend’s Facebook page and virtual lipstick smeared on a user’s character, or avatar. In online gaming, it might include virtual flaming swords for bit-to-byte combat.

Read the rest of this entry »