Yes, according to the Art Newspaper.

A recent spate of high profile thefts suggests that art crime is increasing. The FBI estimates that international art crime, which includes fakes, forgeries and thefts, is now worth more than $6bn annually.

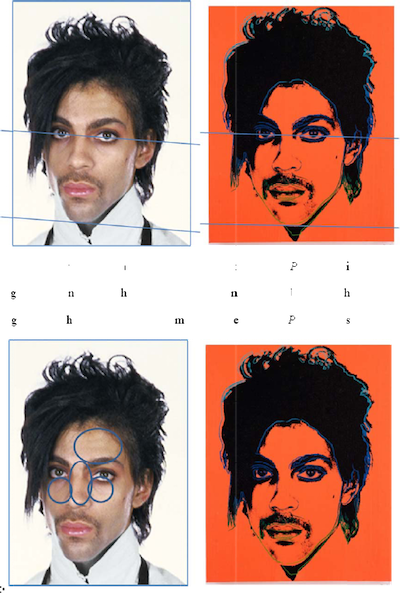

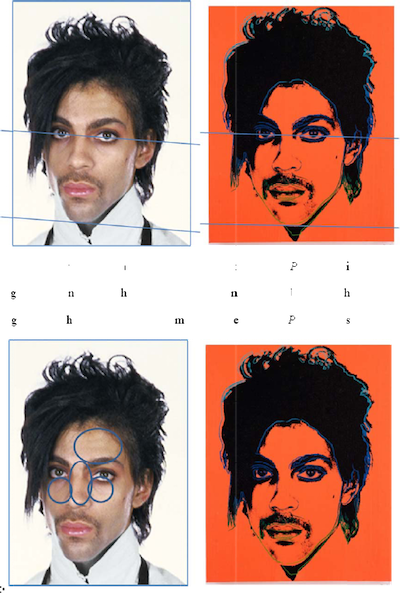

Images of Goldsmith and Warhol at issue. The U.S. Supreme Court will review a ruling that an Andy Warhol print infringed a copyrighted photograph taken by photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, of the late musician, Prince. We certainly hope--as much as one can hope for anything these days--that SCOTUS cleans up the wasteland that has become of "fair use" interpretation. One would think, and hope I suppose, that with many of the sitting justices adhering to textualism, they will fully jettison the nonsensical "transformativeness" test that has plagued us like a really bad case of Covid since the mid-1990s. Docs here, via ...

Ahh...Youth! Sergio Munoz Sarmiento. (2015 - ongoing), C-Print. © and TM Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. All rights reserved. I had a lovely conversation with fellow lawyer and artist, Stephanie Drawdy, on the NFT craze, pets, art law, and the origins of The Art & Law Program. You can listen to the Podcast here. Hope you enjoy!

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou, and the Association Marcel Duchamp have digitized their vast archives of material on the Dadaist and placed it online, where it is free to all. Enjoy!

If you have kids at home and want them to do something fun and educational, try the Art & Law Coloring Book, an ongoing project by The Art & Law Program. Really a great collection of drawings by great artists, including: Emma Jane Bloomfield Damien Davis Molly Dilworth João Enxuto Soda Jerk Clare Kambhu Alexandra Lerman Erica Love Douglas Melini Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento Melinda Shades Elisabeth Smolarz Gabriel Sosa Alfred Steiner Valerie Suter Happy coloring!

If you're confused as to what the hell NFTs are, particularly art NFTs, here's a new article by Alfred Steiner that pretty much walks you through and safely out of the NFT hell. In his article, Steiner explains what NFTs are and what it means to own one. He also discusses why that meaning of ownership—which may appear novel to many—isn’t new at all when considered against the backdrop of the market for conceptual art. Steiner concludes with some observations about how NFTs may be good and bad for the art industry.

Yes, according to the Art Newspaper.

A recent spate of high profile thefts suggests that art crime is increasing. The FBI estimates that international art crime, which includes fakes, forgeries and thefts, is now worth more than $6bn annually.

According to Animal, “[t]he art-world star curators were convicted for offending religion under Article 282 and fined, narrowly escaping being sentenced to time at a gulag-lite.”

A fresco that was restored by so-called experts has somehow lost some of its original content (phalluses and testes). Town officials plan to file charges with the local prosecutor because the restoration effort “did not respect the original character of the work.”

Via Italy Magazine.

I received three e-mails and one text message today asking why we hadn’t posted on the Gordon v. McGinley decision. Our answer, everybody calm down. First of all, it’s not that interesting of a case, and second of all, it borders on frivolous. This is the kind of case that anti-copyright schizophrenics love because (a) it “proves” (to them) that copyright stagnates culture and (2) that the “right” party won (read: the one anti-copyright schizos were rooting for).

But just in case you want a little nugget from the judge’s head, here it is,

[T]he dictates of good eyes and common sense lead inexorably to the conclusion that there is no substantial similarity between Plaintiff’s works and the allegedly infringing compositions of McGinley.

But my favorite is this one. Highlighting that although anyone can be an expert in the field of art, Judge Sullivan pulls no punches when he calls out Dan Cameron:

the substance of the expert affidavits simply underscores the infirmity of Plaintiff’s infringement claim. Several experts profess a belief that Plaintiff should prevail in this action while disavowing any familiarity with copyright law.

Basically (and rightly) concluding,

What is clear from the foregoing expert testimony is not that Plaintiff should prevail in this action, but that the remedy for the instant dispute lies in the court of public or expert opinion and not the federal district court.

It seems that Federal judges are having a field day with artists and art “experts” lately (Richard Prince and Dan Cameron respectively). With ducks lining up in a row, who can blame them?

The opinion is available here.

Our good friend and law professor at Texas Wesleyan School of Law, Megan Carpenter, analyzes the intellectual property issues concerning art museums and their interactive, collaborative, and user-generated exhibitions. In particular, she asks whether these museum strategies run afoul of U.S. Copyright law as well as the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act, otherwise known as moral rights.

She focuses on a recent exhibition by the Dallas Museum of Art, where a sound installation played on speakers throughout the show and responded directly to the works on display. Artist Chapman Kelley publicly objected to the collaborative project, requesting that his work be removed from the exhibition and returned to him. Kelley claimed that the soundscape effectively used his existing work to create a new piece of art without his consent. The Museum refused.

From the SSRN site:

This article explores efforts by museums and galleries to enhance user experience (and increase attendance) using technology to create interactive and engaging exhibitions, and considers the copyright implications of this “participatory museum” movement. From the derivative rights provisions in the Copyright Act to the Visual Artists’ Rights Act, where do the artist’s rights stop and the museum’s obligations begin, and how is the public’s interest best served?

The law review article is was published in the Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, Vol. 13, No. 3, Spring 2011, and can be downloaded here.

Remember the Costco v. Omega fiasco from last winter, where the U.S. Supreme Court, with Justice Kagan recusing herself, went 4-4 regarding the issue of whether the U.S. Copyright Act applied extra-territorially? In that case, the Supreme Court was reviewing a 9th Circuit decision that upheld Omega’s right to prevent Costco from selling legitimate Omega watches it had purchased abroad from a gray-market importer and selling them for much lower cost in the U.S.

Well, yesterday, the 2nd Circuit agreed with the 9th Circuit when it decided 2-1 in John Wiley & Sons Inc. v. Supap Kirtsaeng that it is illegal for anyone to import and sell foreign-made copyright works without the copyright owner’s consent.

Why is this important? Remember Cornell University’s Peter Hirtle, and his argument on what the Costco decision, if upheld, would have for museum exhibitions and the public display of art works? (Note here that Hirtle focuses on the public display of artworks, not just the resale right.) Well, about a year ago I applied Hirtle’s reading to visual artworks. Here’s the reminder:

[I]f the Supreme Court upholds the Ninth Circuit’s decision, it would mean that any museum that wanted to display a foreign work still protected by copyright abroad would have to either get permission from the foreign copyright owner or make a fair use argument, unless they had obtained the copyright with the artwork or obtained permission to display the art work directly from the author and/or copyright owner. I wonder why no one else aside from Hirtle has picked up on this?

With the 2nd and 9th Circuit’s agreeing, and without a circuit split, it seems this reading is the guiding light. Hirtle’s argument may be accessed here.

Thomson Reuters has more here.

It’s bad enough fair use has become the Colosseum of U.S. Copyright law. But starting on January 1, 2013, we may have more copyright litigation concerning a little-known provision of the 1976 Copyright Act. Section 203 of the U.S. Copyright Act, Termination of transfers and licenses granted by the author, states that “[i]n the case of any work other than a work made for hire, the exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license of copyright or of any right under a copyright, executed by the author on or after January 1, 1978, otherwise than by will, is subject to termination[.]”

It’s bad enough fair use has become the Colosseum of U.S. Copyright law. But starting on January 1, 2013, we may have more copyright litigation concerning a little-known provision of the 1976 Copyright Act. Section 203 of the U.S. Copyright Act, Termination of transfers and licenses granted by the author, states that “[i]n the case of any work other than a work made for hire, the exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license of copyright or of any right under a copyright, executed by the author on or after January 1, 1978, otherwise than by will, is subject to termination[.]”

What this basically means is that artists and other creative individuals will generally have the right to reclaim ownership of their creative works made after January 1, 1978, unless they were employees while they created artistic works, or fall under a work-for-hire provision.

According to the NY Times, this provision is bound to be hotly contested in the area of music recordings, particularly when it concerns big music stars like Bob Dylan, The Eagles, and Bruce Springsteen and the big four recording companies. So, where these musicians employees? Not so fast says June Besek, executive director of the Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts at the Columbia University School of Law. Applying “common sense,” we must ask, “Where do they work? Do you pay Social Security for them? Do you withdraw taxes from a paycheck? Under those kinds of definitions it seems pretty clear that your standard kind of recording artist from the ’70s or ’80s is not an employee but an independent contractor.”

I’m a bit short on time right now so I cannot fully digest this situation, but the one question I do have in mind is how this will affect — if at all — visual artists.

Update: August 17, 2011

Village People band member files transfer for his share.

Clancco, Clancco: The Source for Art & Law, Clancco.com, and Art & Law are trademarks owned by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. The views expressed on this site are those of Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento and of the artists and writers who submit to Clancco.com. They are not the views of any other organization, legal or otherwise. All content contained on or made available through Clancco.com is not intended to and does not constitute legal advice and no attorney-client relationship is formed, nor is anything submitted to Clancco.com treated as confidential.

Website Terms of Use, Privacy, and Applicable Law.