What are the differences in the ways different societies conceptualize punishment? What are the differences in the ways they enact it? And what can be learned by looking at other systems of punishment about the contingency and potential for transformation of our own system? Ancient Athens has often served as a model for certain of the modern world’s deepest aspirations in democratic government and philosophical rationality. At least since Nietzsche, it has also sometimes been approached as an extremely foreign land, whose values and practices, in their strangeness, can at the same time show just how strange our own are. How, now, does Athens look when we turn our attention to its conceptualization and enactment of punishment?

Will textualism save our copyright planet? Warhol Fdn v. Lynn Goldsmith headed to SCOTUS

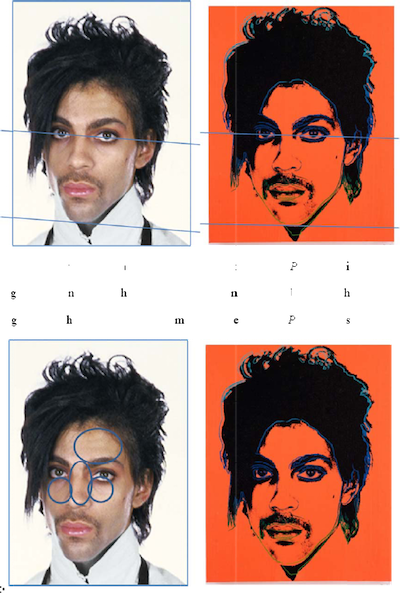

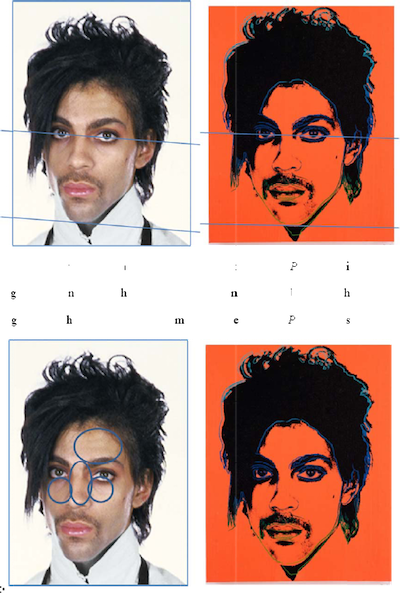

Images of Goldsmith and Warhol at issue. The U.S. Supreme Court will review a ruling that an Andy Warhol print infringed a copyrighted photograph taken by photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, of the late musician, Prince. We certainly hope--as much as one can hope for anything these days--that SCOTUS cleans up the wasteland that has become of "fair use" interpretation. One would think, and hope I suppose, that with many of the sitting justices adhering to textualism, they will fully jettison the nonsensical "transformativeness" test that has plagued us like a really bad case of Covid since the mid-1990s. Docs here, via ...

Podcast: Stephanie Drawdy and Sergio Munoz Sarmiento on All Things Art and Law

Ahh...Youth! Sergio Munoz Sarmiento. (2015 - ongoing), C-Print. © and TM Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. All rights reserved. I had a lovely conversation with fellow lawyer and artist, Stephanie Drawdy, on the NFT craze, pets, art law, and the origins of The Art & Law Program. You can listen to the Podcast here. Hope you enjoy!

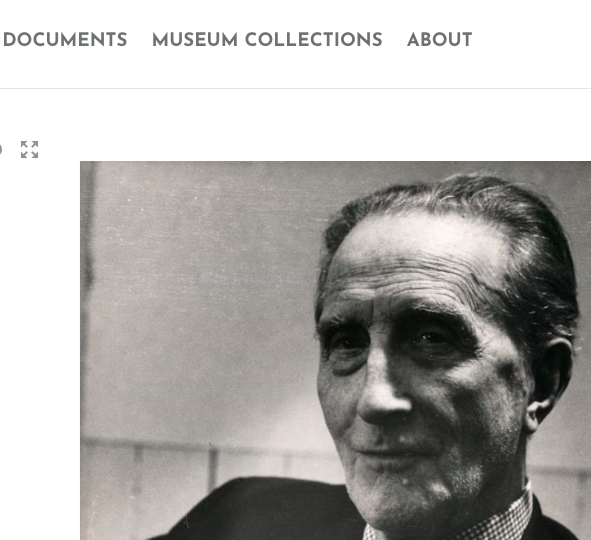

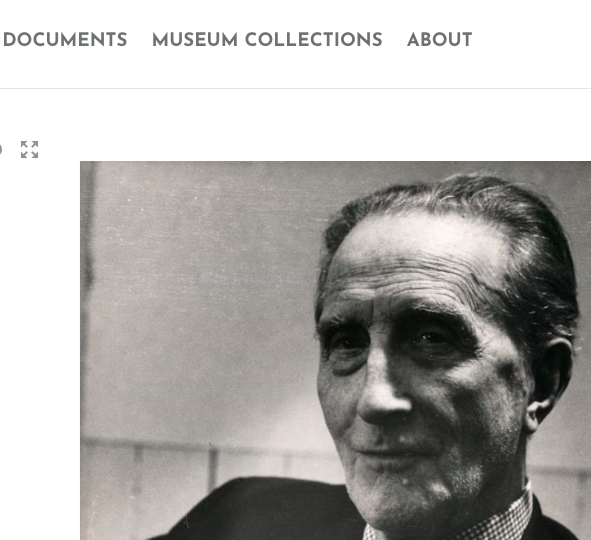

Marcel Duchamp archives now online, free of charge

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou, and the Association Marcel Duchamp have digitized their vast archives of material on the Dadaist and placed it online, where it is free to all. Enjoy!

The Art & Law Coloring Book

If you have kids at home and want them to do something fun and educational, try the Art & Law Coloring Book, an ongoing project by The Art & Law Program. Really a great collection of drawings by great artists, including: Emma Jane Bloomfield Damien Davis Molly Dilworth João Enxuto Soda Jerk Clare Kambhu Alexandra Lerman Erica Love Douglas Melini Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento Melinda Shades Elisabeth Smolarz Gabriel Sosa Alfred Steiner Valerie Suter Happy coloring!

What are NFTs and what does it mean to own one?

If you're confused as to what the hell NFTs are, particularly art NFTs, here's a new article by Alfred Steiner that pretty much walks you through and safely out of the NFT hell. In his article, Steiner explains what NFTs are and what it means to own one. He also discusses why that meaning of ownership—which may appear novel to many—isn’t new at all when considered against the backdrop of the market for conceptual art. Steiner concludes with some observations about how NFTs may be good and bad for the art industry.

We’re taking a much needed holiday break, but we’ll try to keep up with any art law news that arise. Happy Holidays, everyone!

Artist Josafat Miranda has agreed to destroy the paintings he made based on other artists’ photographs.

Artist Josafat Miranda has agreed to destroy the paintings he made based on other artists’ photographs.

“I didn’t steal these images,” Miranda told the [Artinfo] in his defense. “My only mistake was not giving the original artists credit. I’ve now spoken to them and apologized to them. We came to the agreement that I have to take everything down and destroy it, which is exactly what I’m going to do.”

This makes no sense. If Miranda actually believes his only mistake was lack of accreditation, why destroy the work? My guess is that Miranda knows quite well that his work is not simple plagiarism, but rather outright copyright infringement.

Yes, there are artists out there whose practice is based on mimicking or copying other artists works. The difference is that these artists make it quite clear that copying is at the crux of their conceptual praxis and, more importantly, they don’t attempt to pass off their work as original.

This was just plain dumb.

Via Artinfo.

I should clarify. The question should be, who owns the copyright to a tattoo designed by the tattoo artist?

I should clarify. The question should be, who owns the copyright to a tattoo designed by the tattoo artist?

Most copyright lawyers, and enthusiasts, would know that sans a copyright transfer, the copyright belongs to the tattoo artist. So, what’s the big deal?

Well, this case, Escobedo v. THQ, Inc., throws an interesting wrench in the copyright machine. The case concerns a mixed martial arts fighter, Carlos Condit, who allegedly licensed his right of publicity to a video game company. So far, so good, right? Well, there’s a little snag which you probably figured out already. Condit has a tattoo of a lion inked on his torso, and the video game depicts Condit with the lion tattoo (presumably true-to-life).

The tattoo artist, Chris Escobedo, has filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court of Arizona for copyright infringement against THQ, Inc., the makers of the hit mixed martial arts (“MMA”) video games UFC Undisputed and UFC Undisputed 3.

The Legal Satyricon‘s Marc John Randazza has THQ, Inc. winning based on some weird notion of “fairness.” Rendazza agrees that Escobedo owns the copyright to the lion tattoo, but argues that THQ has a fair use argument based on their acquisition of Condit’s publicity rights. In other words, THQ purchased the rights to the tattoo when they purchased Condit’s publicity rights.

This argument is flawed. If true, it would mean that a celebrity (or rock star) who consistently wears a t-shirt with a Mickey Mouse emblazoned on it would grant a video maker the rights to the Mickey Mouse simply because the Mickey t-shirt had become synonymous with the celebrity. This is ridiculous. There are many examples countering Randazza’s argument. The main one that comes to mind is film. Film makers must do the same for underlying works when shooting the interior of someone’s home or private property. Simply obtaining a property release would not absolve the filmmaker from copyright liability for capturing copyrighted paintings, sculptures, drawings, posters, murals, etc. (I also recently blogged about the artist who designed the first Baltimore Ravens logo and his win against the video game maker.)

Randazza argues that if Escobedo were to prevail, it would mean that every tattoo customer who wished to own the copyright to a tattoo designed by the tattoo artist would have to obtain a signed copyright transfer from the tattoo artist. Yes, that’s right. It’s not that hard. Collectors and museums must do the same when they purchase an artwork from an artist and simultaneously wish to obtain the copyright to the artwork.

I’ll add what every avid sports fan knows: these days athletes are memorable not only for their feats, but also for their “tough guy” brand (see Allen Iverson and the NBA’s airbrush deletion of Iverson’s tattoos).

My call? On the fair use question, and assuming no clean title claim by Condit, Escobedo wins.

More via PR Web.

“They said I was trespassing,” [the artist said]. “When I showed them my ticket, they said I was displaying art.”

Maybe if the artist, F. Geoffrey Johnson, had had a monkey produce his art he’d be allowed to exhibit his artwork without fanfare.

Via Artinfo.

The market for Salvador Dalí’s sculptures remains plagued by misinformation, unauthorized editions, ownership disputes, and some outright fraud. Questionable works are still flooding the market.

Via Art News.

This case has a bit of history. Artist Frederick Bouchat had previously won a copyright infringement lawsuit against the NFL, alleging that the Baltimore Ravens had used part of his drawing without permission. Although he won the fight, he lost on the damages argument (the jury awarded no damages to Bouchat, finding that no part of the NFL ‘s profits were attributable to the infringement. The Ravens stopped using the infringing logo in 1998.).

This case has a bit of history. Artist Frederick Bouchat had previously won a copyright infringement lawsuit against the NFL, alleging that the Baltimore Ravens had used part of his drawing without permission. Although he won the fight, he lost on the damages argument (the jury awarded no damages to Bouchat, finding that no part of the NFL ‘s profits were attributable to the infringement. The Ravens stopped using the infringing logo in 1998.).

Fast forward to a football video game, created by EA Sports, which featured “throwback” uniforms of football teams. You guessed it. The video game allowed players to pick the Baltimore Ravens uniform from 1996, complete with the infringing Flying B logo.

Outcome? A federal district court in Maryland determined that EA Sports’ use of Bouchat’s Baltimore Ravens’ logo in its “Madden NFL” game was not a fair use. It remains to be seen whether Bouchat will be awarded monetary damages for this infringement.

Via JD Supra. The article briefly discusses the four fair use factors.

Clancco, Clancco: The Source for Art & Law, Clancco.com, and Art & Law are trademarks owned by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. The views expressed on this site are those of Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento and of the artists and writers who submit to Clancco.com. They are not the views of any other organization, legal or otherwise. All content contained on or made available through Clancco.com is not intended to and does not constitute legal advice and no attorney-client relationship is formed, nor is anything submitted to Clancco.com treated as confidential.

Website Terms of Use, Privacy, and Applicable Law.