German artists have taken issue with Google’s Image Search program, and so far won a German court ruling against Google for copyright infringement. This is certainly a case to keep an eye on, as it may dictate how copyright law splits when it comes down to national borders. Although U.S. courts have already ruled in favor of Google on this particular issue, the question of its international veracity is still unknown.

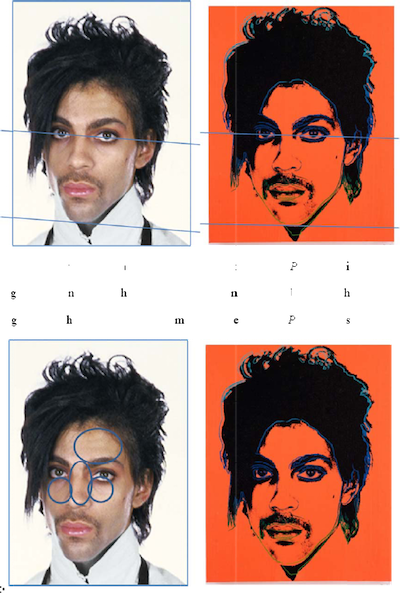

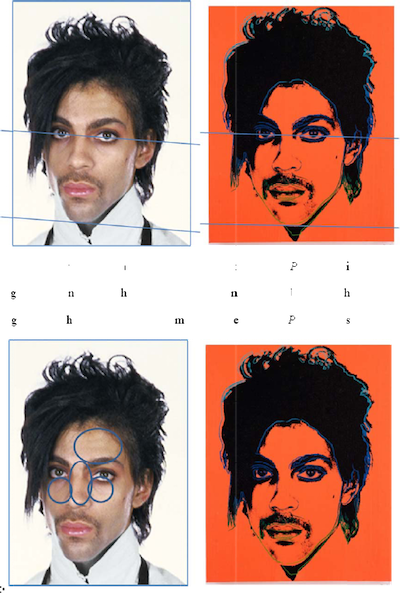

Will textualism save our copyright planet? Warhol Fdn v. Lynn Goldsmith headed to SCOTUS

Images of Goldsmith and Warhol at issue. The U.S. Supreme Court will review a ruling that an Andy Warhol print infringed a copyrighted photograph taken by photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, of the late musician, Prince. We certainly hope--as much as one can hope for anything these days--that SCOTUS cleans up the wasteland that has become of "fair use" interpretation. One would think, and hope I suppose, that with many of the sitting justices adhering to textualism, they will fully jettison the nonsensical "transformativeness" test that has plagued us like a really bad case of Covid since the mid-1990s. Docs here, via ...

Podcast: Stephanie Drawdy and Sergio Munoz Sarmiento on All Things Art and Law

Ahh...Youth! Sergio Munoz Sarmiento. (2015 - ongoing), C-Print. © and TM Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. All rights reserved. I had a lovely conversation with fellow lawyer and artist, Stephanie Drawdy, on the NFT craze, pets, art law, and the origins of The Art & Law Program. You can listen to the Podcast here. Hope you enjoy!

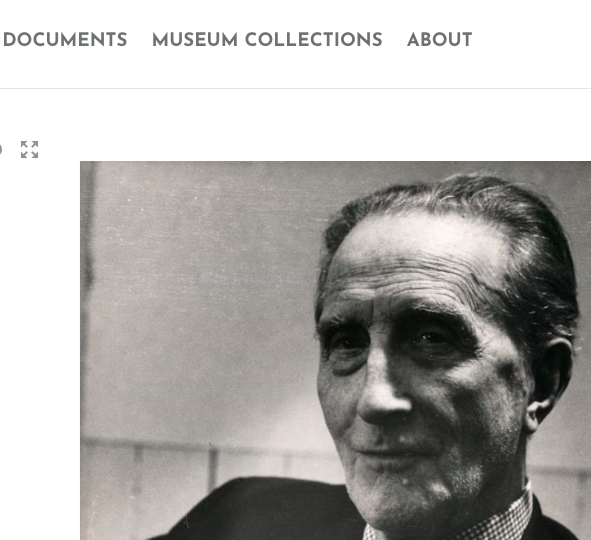

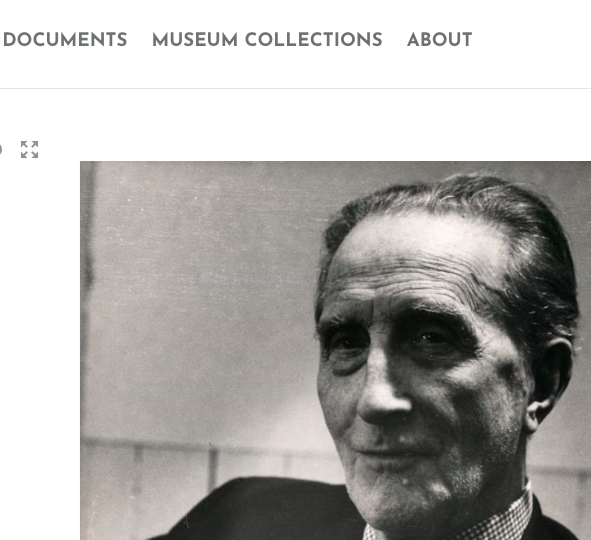

Marcel Duchamp archives now online, free of charge

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Centre Pompidou, and the Association Marcel Duchamp have digitized their vast archives of material on the Dadaist and placed it online, where it is free to all. Enjoy!

The Art & Law Coloring Book

If you have kids at home and want them to do something fun and educational, try the Art & Law Coloring Book, an ongoing project by The Art & Law Program. Really a great collection of drawings by great artists, including: Emma Jane Bloomfield Damien Davis Molly Dilworth João Enxuto Soda Jerk Clare Kambhu Alexandra Lerman Erica Love Douglas Melini Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento Melinda Shades Elisabeth Smolarz Gabriel Sosa Alfred Steiner Valerie Suter Happy coloring!

What are NFTs and what does it mean to own one?

If you're confused as to what the hell NFTs are, particularly art NFTs, here's a new article by Alfred Steiner that pretty much walks you through and safely out of the NFT hell. In his article, Steiner explains what NFTs are and what it means to own one. He also discusses why that meaning of ownership—which may appear novel to many—isn’t new at all when considered against the backdrop of the market for conceptual art. Steiner concludes with some observations about how NFTs may be good and bad for the art industry.

A Clancco reader, Jeff Stark, commented on a previous story detailing the legal battle between John Chamberlain and Gerard Malanga regarding an alleged fake Warhol. Stark pointed us to a website by Joe Simon-Whelan, which delineates Simon-Whelan’s battle against the Warhol foundation, their dealer Vincent Fremont and its arm the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board Inc.

On October 11th, The Financial Times’ Georgina Adams wrote a lengthy article on the authenticating process of art works, and the legal issues and lawsuits raised by this seemingly random and chaotic process. Simon-Whelan’s lawsuit is mentioned here, along with three other authentication lawsuits.

The Jakarta Post reported on Monday that the the East Denpasar Police summoned a group of young artists for using symbols of the now defunct communist party during an art exhibition organized this past September.

In this week’s The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl reviews two books on the notorious forger of Old Masters, Han van Meegeren: “The Forger’s Spell: A True Story of Vermeer, Nazis, and the Greatest Art Hoax of the Twentieth Century,” by the science journalist Edward Dolnick, and “The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren,” by the writer and artist Jonathan Lopez.

Art forgery is among the least despised of crimes, except by its victims–the identity of those victims being more than exculpatory, for many people. Art is unique among universally esteemed creative fields in its aloofness from a public audience. Its economic base is a club of the wealthy, who share power to impose or repress value with professional and academic élites. Lopez’s muckraking of van Meegeren scants a fact that Dolnick merrily exploits: the forger gratifies class resentment precisely because he is a pariah. Unlike the subversive gestures of a Marcel Duchamp, say, his outrages will not become educational boilerplate in museums and universities. They are impeccably destructive, tarring not only pretensions to taste but the credibility of taste in general. The spectre of forgery chills the receptiveness–the will to believe–without which the experience of art cannot occur. Faith in authorship matters.

James Fenton’s review of these two books, Victims of Vermeermania, appears in the most recent New York Review of Books (unfortunately the review is only accessible by subscription).

Jackie Battenfield asks if it’s true that a work of art created in a nonprofit space receives no copyright protection. She points to the story on this blog. For the sake of saving digital ink, we will reinforce Donn Zaretsky’s argument that “There’s a technical legal term for that: crazy talk.” Donn continues:

Now, there may well have been good reasons for concluding that a lawsuit wasn’t worth pursuing here, but it’s simply not the case that this work was somehow ineligible for copyright protection because it was done “in a nonprofit context.”

Think about it. If this were true, then thousands of artists making art in nonprofit art spaces and museums would be making art that anyone (including corporations such as Anthropologie) could steal for their own (commercial) gain. What artist in their right mind would willingly abdicate any proprietary right to their artistic asset(s) for the privilege of exhibiting in a nonprofit space? Perhaps John Koegel can clarify this misunderstanding.

The full story, with images, can be viewed here.

An Oklahoma City council has — once again — authorized the use of public money for the fabrication and installation of a religious statute. The statute, Come Unto Me (not “come on to me”), by artist Rosalind Cook, depicts a “larger than life [Jesus] Christ figure,” which can be supplemented by, get this, “children of varied nationalities that can be purchased to group with the sculpture.” From Townhall.com:

A conservative Oklahoma City suburb with a history of trying to incorporate religious art into public spaces has approved city funds to help pay for a statue of Jesus Christ to be placed downtown for Christmas, likely leading to another court fight.

“This is the third major unconstitutional effort they’ve engaged in recent years,” said Barry Lynn, executive director of the Washington D.C.-based Americans United for Separation of Church and State. “It’s a little surprising, because normally people pause to take a breath before they violate the Constitution again.”

June Cartwright, the chair of the commission and who supported funding the latest statue, said the sculpture was viewed simply as a piece of art and not a religious endorsement. “It is a piece of artwork,” Cartwright said. “It doesn’t state that it is specifically Jesus. It is whatever you perceive it to be.”

“You cannot promote what is obviously a very specific religious image using tax dollars,” Lynn said. “The city lawyers should have stopped this. This isn’t even close to the line. This is way over it.”

Interesting story in this week’s New York Magazine concerning an outlaw artist. Seems that this artist, Poster Boy (aka vandal under NY law), appropriates and reconfigures subway advertising posters to make political statements. According to the Magazine, Poster Boy dropped out of a “reputable art school” as well as recovering from the current ongoing disease of “making things for bored rich people to hang above their couch.” Seems this rebirth was partially sparked by his introduction to Noam Chomsky, Lao Tzu, and George Orwell. “Books like Animal Farm and 1984 sparked something,” he says. “A new sense of independence, where I felt, I should take control of my environment.”

In January of this year, after dropping out of a reputable art school, he began loitering around the cavernous subway stations that link his Bushwick apartment to his Chelsea-art-studio day job. “I was playing with the posters, cutting them up, ’cause I have to use razors a lot at my job,” he says. His earliest works were hastily assembled, full of floating heads and juxtaposed slogans. But by the spring he was incorporating social critiques, rearranging the Iron Man logo into IRAN=NAM, and altering an NYPD recruitment-drive poster to read MY NYPD KILLED SEAN BELL.

Read the entire New York article here.

Clancco, Clancco: The Source for Art & Law, Clancco.com, and Art & Law are trademarks owned by Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento. The views expressed on this site are those of Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento and of the artists and writers who submit to Clancco.com. They are not the views of any other organization, legal or otherwise. All content contained on or made available through Clancco.com is not intended to and does not constitute legal advice and no attorney-client relationship is formed, nor is anything submitted to Clancco.com treated as confidential.

Website Terms of Use, Privacy, and Applicable Law.