My dear and close friend, Donn Zaretsky, over at his blog, mentions Joerg Colberg’s “challenge” to the artworld (where Colberg asks the “artworld” whether stealing a wallet is the same as appropriation), and writes,

Without taking a position on any particular example of appropriation, let me answer his question with a question: What if, after I took your wallet, you still had your wallet? Would it change your view at all? Would you still call it theft?

Well, as long as the wallet isn’t owned by a biker. But I digress.

I love this hypothetical, straight out of the fictional world that is a law school classroom, seeking to manipulate the reader by proposing an impossibility. Assuming we live in the real world and not a Star Trek episode, there is (currently) no humanly possible way that I can take someone’s Aston Martin and simultaneously leave the Aston Martin’s owner with her car. Absolutely impossible. So, why use this analytical aphrodisiac?

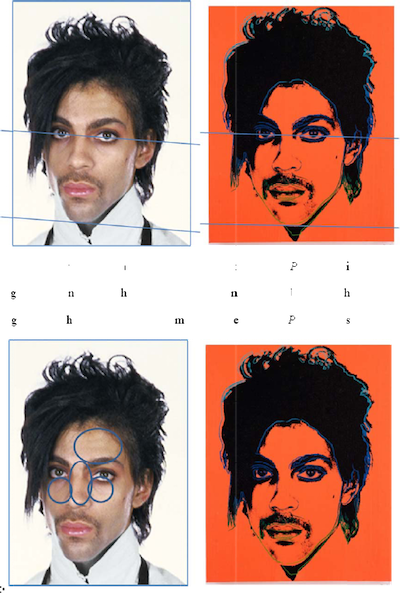

The rabbit in the hat to this argument is this. If I photocopy or rephotograph a copyrighted image exactly as it is, or with little to no transformative change, and use it to make paintings, t-shirts, mugs, postcards, or heck, even three-dimensional sculptures, then what harm is there to the copyright holder of that image? Presumably, none. The original copyright holder still has the image. True, but not so fast. Maybe there is a similarity.

You see, although the original image owner still has her same and “original” image, she has lost some use and rights over her property. How can that be?

Well, we don’t use property law to dissect the above scenario; we use intellectual property law (with the term intellectual being key, meaning that it is, unlike real property, intangible), and thus, we apply copyright’s “fair use” schema and its four non-exclusive factors. The key factor, for me, under this hypothetical analysis, is factor #4 of fair use, market harm (the effect of the use upon the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work).

Simply put, the secondary user has taken (to revert back to real property) at least one of the following rights — granted under copyright law — from the original copyright holder: the right to grant permission, the right to potentially gift it (and thus gain the accolades as explained by Marcel Mauss), the right to potentially license the image to the secondary user, the right to potentially sell the image to the secondary user, the right to potentially never publicly display or publish the image ever again, and/or the right of the original copyright holder to potentially make a similar work to that of the secondary user (a derivative right). So maybe there is a similarity between tangible and intangible property: we’re still denying the original rights holder one property right.

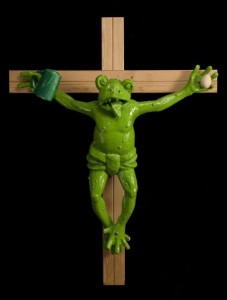

But be careful. This tricky little hypothetical is sometimes used by the free culture party when talking about the death of creativity and culture. Their argument is this. That if third-world children, dying of AIDS, could be saved by unlawfully “appropriating” medical patents from Pfizer, then surely that means that appropriationists (or secondary users) are also morally and legally exculpated when taking copyrighted images without consent, or without having to apply current fair use standards under US Copyright law. Let me spell this out for you: the wallet hypothetical and the death/creativity hypothetical are very, very different. In other words, although the tangible-intangible property argument is plausible, the death/creativity one is not. The death/creativity hypothetical provides for two very different factual scenarios (death vs. cultural creation), with different legal doctrines (patents vs. copyrights), and with very different mediums of appropriation and expression (narcotics vs. images).

Regardless, the “what ifs” are fun to play. Heck, I often wonder, “what if I, 5′ 9″, 165lbs, and a 5 seconds flat in the 40-yard dash, could play middle linebacker for the NY Jets?” That’s fun to ponder, but not gonna happen. What does happen is that my friends and I play football at the local park, and we call ourselves the Williamsburg Copyrights — and best of all — I play both middle linebacker (we play a 4-3) and quarterback. Take that free culturists!