The annual legal problems in museum administration conference was held last month. A few “hot” topics hit the agenda. Not surprisingly, copyright and fair use was in the mix. Other topics were federal resale rights, moral rights, and broken donor pledges. On the current “hot” topic concerning the academic and institutional use of copyrighted images, Theodore Feder, president of New York’s Artists Rights Society, had this to say.

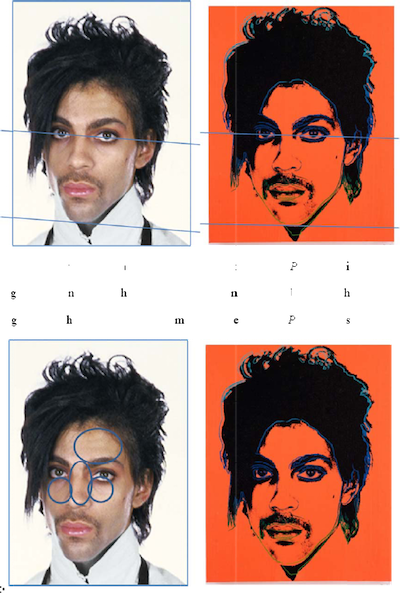

[T]he society accepts “the use of thumbnails before, during and after an exhibition.” Under US “fair use” rules, which allows for the reproduction of copyrighted works in certain educational and other circumstances, “we accept as fair use a scholarly publication of under 3,000 copies [but] not a coffee table book,” plus reproductions used in research and news reporting[.]

The conference was organized by the American Law Institute-American Bar Association and sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and the American Association of Museums. More via The Art Newspaper here.