Should Government Criminalize Violent Artistic Expression?

Think of an artwork, song, film, video, poster, or photograph. In fact, with the omnipresence of social media, think of expression that any person—layperson or self-proclaimed artist—may disseminate into public space and which may be perceived as threatening to a group or individual. The creator of this expression may believe that her expression is just a “passive” and aesthetic expression of her thoughts and feelings and not an expression with intent to cause actual harm to a person or group. However, that person or group may believe, right or wrongly, that the expression constitutes a true threat against them. How then do we assess whether this threatening expression is in fact “true”?

In November 2013, a Pennsylvania trial court convicted a young, black rap artist, Jamal Knox, aka “Mayhem Mal,” for terroristic threats, witness intimidation, and conspiracy to commit terroristic threats. Knox appealed his conviction but the Pennsylvania Supreme Court affirmed the trial court. The conviction was based solely on the content of a song created in 2012 by Knox and Rashee Beasley, aka “Soldier Beaz,” that was uploaded to Facebook and Youtube. Knox’s song, “Fuck tha Police”—an obvious homage to NWA’s seminal 1988 release—contains lyrics about police generally as well as two Pittsburgh police officers who were involved in arresting Knox in 2012. The song lyrics expressed, in part, “I’ma jam this rusty knife all in his guts and chop his feet,” “artillery to shake the mother fucking’ streets,” and in relation to a police officer’s “shift over at three and I’m gonna fuck up where you sleep.” A Pittsburgh police officer who had been monitoring Knox and Beasley’s online presence discovered the song three days later, leading to the criminal charges against Knox and Beasley.

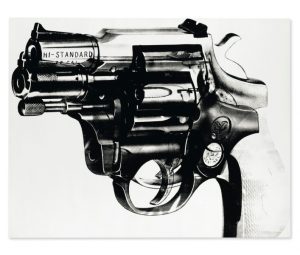

Can we objectively believe that Knox’s song constitutes a true threat? I don’t think so. In fact, Knox’s song presents us with a long standing tradition not only in rap but also other music genres (think heavy metal, punk, country) of including what some individuals deem to be violent and threatening lyrics. (The list of songs including “violent” and “threatening” lyrics is of course endless. The author encourages readers to list their suggestions in the comments box to this article.) Indicative of this misreading is the Pennsylvania courts’ focus on only the lyrics of “Fuck tha Police” without paying any due attention to the musical composition and the musical elements of the singing. By intentionally neglecting these two crucial elements of the song, the poetic nature of Knox’s “Fuck tha Police”—i.e., the artistic expression—is butchered, if not completely obliviated. Taken out of its aesthetic and musical context, arguing that the lyrics in a song alone constitute a “true threat” is tantamount to claiming that when the Museum of Modern Art exhibits Andy Warhol’s Gun (1988) it is using a weapon in a threatening manner (a criminal offense).

(Andy Warhol. Gun, 1981-1982)

There is widespread disagreement among federal and state courts as to how to assess whether a statement is a “true threat” and thus unprotected by the First Amendment. Most courts apply what is called an objective standard, where the government is required to show that a reasonable person would regard the statement as a sincere threat. A minority of courts apply the subjective standard, which requires the government to show only the speaker’s intent to threaten. The U.S. Supreme Court had provided us with an answer to this question before, holding, in Watts v. United States (1969) that the First Amendment protects statements that a reasonable person would not regard as threatening. However, as often happens in Supreme Court jurisprudence, in a 2003 case, Virginia v. Black, concerning the constitutionality of a Virginia statute that criminalized the burning of a cross in public view “with the intent of intimidating any person,” the U.S. Supreme Court confused years of precedent by holding that true threats were “those statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals.” This confusion led some courts to read Black to mean that the standard now is purely subjective, and thus the government must show only the speaker’s subjective intent to threaten. Both Pennsylvania courts applied the “subjective” test in convicting Knox.

Through his law firm, Arnold & Porter, Knox appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court last week. The Court will soon decide whether or not to hear Knox’s appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court should hear this case and clarify when a statement actually constitutes a “true threat.”

There have also been four amicus curiae briefs (“friend of the court” briefs) in support of Knox: one filed on behalf of other rap artists and one on behalf of law professors, curators, legal and artistic practitioners and art historians committed to protecting the First Amendment rights of all speakers and artists. In full disclosure, I have signed on to the latter brief, spearheaded by Erin Murphy of the law firm Kirkland & Ellis, which argues that a context-sensitive inquiry into whether speech constitutes a punishable “true threat” is necessary to safeguard our freedom of expression. Two additional amicus curiae briefs were also filed, one by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and another jointly by the Cato Institute and The Rutherford Institute.

Allowing the government to regulate expression that is in fact threatening to a person or group is reasonable. However, and as with any form of government action, this permission to regulate must be narrowly tailored. Allowing the government to convict and incarcerate individuals for expression that is not objectively threatening will restrain artistic speech and is contrary to First Amendment principles. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court itself agreed, stating in Virginia v. Black that a ’hallmark’ of the constitutional right to free speech is “to allow ‘free trade in ideas’—even ideas that the overwhelming majority of people might find distasteful or discomforting.”

It is bad enough that we live in a time where some artists are censoring speech and demanding the destruction of art. For this moral imperative to be legally enforced and criminally punished is beyond the rule of law and the dictates of the U. S. Constitution.

The case is Jamal Knox v. Pennsylvania.

Tags: amicus brief, artlaw, Free Speech, jamal knox, mayhem mal, rap music, sergio munoz sarmiento, true threat, us supreme court

Comments