Concealment and Law in the Work of Carey Young

Carey Young’s art projects–invoking legal language and procedures–highlight the connection between law and visual culture without divorcing themselves from art historical discourses. Young’s work revolves around the role of categorization, narrative, and rhetorical/linguistic contestations. In particular, Young’s work seeks to elucidate how these three modes of linguistic production function not only within legal frameworks, but also how they in turn frame and are framed by other cultural discourses.

(Disclaimer series as installed at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds (2004). Image courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York)

As one example, Young’s Disclaimer series, Disclaimer: Ontology, Disclaimer: Access, and Disclaimer: Value, consists of three medium-sized white panels containing language that directly stipulate, and thus categorize, the legal relationship between artist and collector, and between artist and cultural institution. Reminiscent of Joseph Kosuth’s early work, Art as Idea as Idea, where Kosuth directly represents and defines the characteristics inherent in the artwork, and Ashley Bickerton’s self-referential wall sculptures from the late ’80s, Young’s Disclaimer series warn viewers and potential collectors of implied assumptions inherent in a work of art.

(Carey Young/Massimo Sterpi, Disclaimer: Value, 2004. Image courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.)

(Ashley Bickerton, Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles), 1987-88)

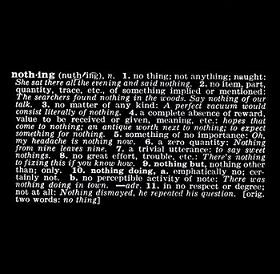

(Joseph Kosuth, Art as Idea as Idea, Nothing, 1967)

Although Kosuth and Bickerton’s strategies are also present in Young’s work, the main issue raised in the Disclaimer series is the question of legality, particularly as it applies to the “warranties” stipulated by Young. In Disclaimer: Value, the stipulation, “The artist does not guarantee that this piece can be sold as a work of art” clearly indicates that this particular (art) object, if sold, should not necessarily be bought with the assumption that it is an artwork or that it contains artistic or monetary value. The “piece” can be bought, but may be bought as an object with multiple uses, none of which may relate in any which way to art or an art object. In fact, Young is ridding herself of any complaints that could be made by her gallery representatives that the work is not apt for sale as a “work of art.” Simultaneously, Young dispenses with any potential critical claims that what she is producing and selling is not art or worthy of being seen or valued as art. Pushing Frank Stella’s famous epigram one step further, Young warns, “What you buy is what you buy.”

Of course, whether or not these disclaimers would have any legal merit in a court of law is questionable. Presumably not, and that is simultaneously the weak and strong point of these art objects. Weak in that the work still remains within a representational framework, where the work seeks to illicit a particular conceptual and intellectual dialogue in a viewer and consumer through the indexing of another linguistic structure and culture–that of the force of law. From this indexing comes its strength. Similar to Lawrence Weiner’s text pieces, the work highlights the implied assumptions by viewers, collectors, critics and artists about the implied expectations of an art object and its relationship to art historical discourse. By announcing its disclaimers as such, Young points out–through legal discourse–those assumptions we carry about an art object, but conversely demonstrates the impotence of art vis-à-vis the force of law. Young poignantly highlights that in the end, an artwork, labeled and contextualized as such, is limited not only by its own historical framework–discursive, economic, and physical — but also by the impotence of its “objecthood.”

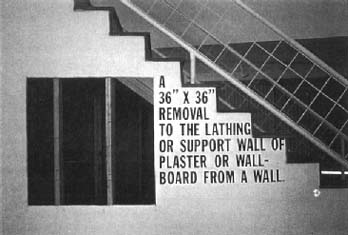

(Lawrence Weiner, A 36″ x 36″ Removal to the Lathing or Support Wall of Plaster or Wallboard From a Wall, 1968)

One aspect of narrative is that it functions as a pleading or story used to persuade someone to believe or to do something.

Through her interest in and use of “legal” lexicon, Young indicates the failure of literal linguistic narrative to deliver understanding and a visual image of the social and legal predilection in which the reader/signor finds herself. Where Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ text based works depict a visual image for the reader–at times general and at other times personal–Young illustrates how language that is supposed to serve a public purpose by providing clear and unambiguous meaning(s) fails to provide any clear and direct representational imagery.

(Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (I Love NY), 1991. C-print jigsaw puzzle in plastic bag. 10 ½ x 13 ½ inches. Edition of 3, 1 A.P., Photo: Oren Slor. © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation. Courtesy: Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York)

Take for instance Cautionary Statement.

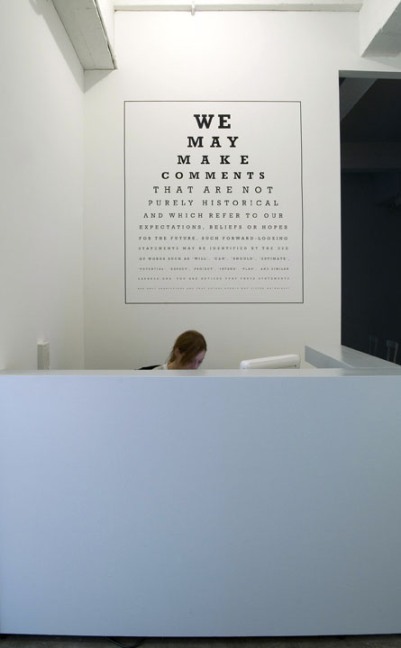

“We may make comments that are not purely historical and which refer to our expectations, beliefs or hopes for the future. Such forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of words such as ‘will’, ‘can’, ‘should’, ‘estimate’, ‘potential’, ‘expect’, ‘project’, ‘intend’, ‘plan’, and similar expressions. You are advised that these statements are only predictions and that actual events may differ materially.”

(Carey Young, Cautionary Statement, 2007. Installation view. Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York)

Using a Snellen Chart format, Young highlights the concealed presuppositions ingrained within legal statements and utterances; how specific words are coded with implicit and binding meanings within a broader system of legal symbolism, where the veiled effects of this language can only be made apparent to those (well) versed in legal culture and language. That these future comments may be identified by certain terminology (will, can, should, estimate, etc.) that, if read as such, are to be read only as future predictions which may differ in the actual, and future, outcome, thus bankrupting the purpose of clear contractual language. This bankrupting process serves the purpose of the contract’s drafter, usually the party in a higher position of power and financial status. Who is making the comments, and specifically, which comments? Whose expectations, beliefs, and hopes? What is a material difference? According to whom? What’s the standard? What is the purpose of ambiguity veiled in seeming clarity?

(Carey Young, Cautionary Statement, 2007. Vinyl text. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York)

In a sense, it is the effects created by concealed meanings, stemming from our investment in legal codes and courtroom tactics, that Young touches upon. Without these concealed meanings, it is likely that human interaction would not be possible, at least not within the nexus known as the social contract. Although we have the ethical mandates of a promise, without a force of law the promise is just that, a promise without threat and without a capacity to enforce or restrict actions.

These same legal skills, tactics and positioning maneuvers are also waged within the broader spectrum of visual culture (and of course culture itself, of which law plays a major part). However, within the field of culture, the legal mechanics exploited by Young are simultaneously reflected and mimicked in the production and reception of culture. Take for instance art school dynamics. One can certainly recall certain studio or group critiques where the “presenter” took the position of defendant, and the instructor and peers that of prosecutors. To another extent, the legal dynamics of ambiguous yet aggressive rhetorical skills are present in everyday cultural products and media: from café receipts and apartment leases, to website disclaimers and storefront ads.

Young’s work, particularly Cautionary Statement and the Disclaimer Series, highlight Anthony J. Amsterdam and Jerome Bruner’s argument in their book, Minding the Law, that “[c]ultures in their very nature are marked by contests for control over conceptions of reality.” (231)

Tags: art and law, ashley bickerton, carey young, Contracts, critical theory, eye chart, felix gonzalez torrest, joseph kosuth, lawrence weiner

Comments