On Law, M&M’s, and the Panopticon: The Work of Donny Johnson

Ruben Verdu’s project raises timely issues not only of incarceration, confinement and the state apparatus, but also of sovereignty and expression.

An apt and current example of the functions of such state power is the recent case of Donny Johnson, a 46 year-old prisoner in California’s maximum security prison Pelican’s Bay.

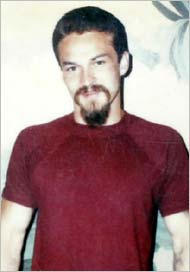

(Donny Johnson, 1985, San Quentin)

(Donny Johnson, 1985, San Quentin)

According to reports by the New York Times and The Mercury News, Johnson is serving three life sentences after he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in 1980 for a drug-related killing, drawing a sentence of 15 years to life. In 1989, he was convicted of slashing the throat of one guard and assaulting another. Those crimes resulted in two additional sentences of nine years to life.

Johnson has been in solitary confinement in a small 8 foot by 12 foot concrete cell for almost two decades. His meals are pushed through a slot in the door. Except for the odd visitor, with whom he talks through thick plexi-glass, he interacts with no one. He has not touched another person in 17 years.

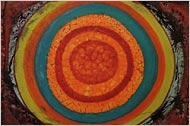

Johnson is also an artist. He paints with a brush he created with plastic wrap, foil and his own hair. He makes paint by leaching the colors from M&M’s in little plastic containers that once held packets of grape jelly. His canvases are postcards.

Johnson is confined in the x-shaped Security Housing Unit (SHU), a level four maximum security area. A short description of SHU:

As with its 18th-century ancestor, the key to control within the SHU is to minimize human contact and maximize sensory deprivation. A Pelican Bay SHU inmate is guaranteed at least 22’/~ hours of bleak confinement. Almost half of the cells, designed for one prisoner, are now overcrowded with two men per cell. The SHU prisoner has little or no face-to-face contact with others-not even with guards who have been largely replaced by round-the-clock electronic surveillance. The inmate sits in a windowless cell with a poured concrete sleeping slab, immobile concrete stool, small concrete writing platform behind a thick, honeycombed steel-plated door. Guards monitor him from control booths with video cameras and communicate through speakers. A SHU prisoner never sees the light of day. He may not decorate his white cell walls. He has no job, educational classes, vocational training, counseling, religious services, or communal activities. No hobbies are permitted to help pass the time. The prisoner eats in his cell from a dinner tray passed through a slot in the door. Once a day he may exercise alone in a small, indoor, bare “dog walk’; without exercise equipment, toilet, or water. He is strip-searched before and after this strictly monitored exercise. Because each of the 132 eight-cell pods has its own exercise area, this procedure is more a ritual of humiliation than a security precaution. Whenever a prisoner is moved from place to place, he is handcuffed before exit from his cell, shackled hands to waist, hobble-chained ankle-to-ankle, accompanied by two guards, and observed on video monitors.

(The Crime of Punishment: Pelican Bay Maximum Security Prison, by Corey Weinstein and Eric Cummins). .

The New York Times and The Mercury News have reported that Johnson was disciplined in the late summer of 2006 for engaging in “unauthorized business dealings.” Pelican Bay officials allege that in order to maintain peace and secure prison conditions, prisoners are prohibited from engaging in “a business or profession without the warden’s permission.” So in what business was Johnson engaged?

Earlier this past summer, Johnson exhibited 25 of his post card paintings in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, of which he sold six at a price of $500 each. Since the prison will not allow Johnson to keep the proceeds, Johnson donated the money to the Pelican Bay Prison Project, a nonprofit group that focuses on helping children of prisoners.

Even though Johnson was not keeping any of the proceeds, the prison defines a business as “any revenue-generating or profit-making activity.” This narrowly tailored definition, along with the little first amendment protection afforded to prisoners makes Johnson’s battle for his right to engage in art making and donative activities nearly insurmountable. Although the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits cruel and unjust punishment, and the First Amendment’s free speech clause has been interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court as encapsulating artistic expression, prisoners enjoy a significantly lower level of first amendment protection.

Also this past summer, in Beard v. Banks, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a Pennsylvania prison rule denying prisoners access to personal photographs as well as secular magazines and newspapers. Prison officials asserted that the ban on newspapers, magazines, and personal photographs served to “motivate” better behavior by creating incentives, “minimize” the amount of personal property and make it easier to detect contraband, and “diminish” the amount of raw material that prisoners might use to fashion attack weapons (spears, blowguns, or catapults for hurling objects). The Supreme Court decision in Turner v. Safley affords considerable deference to prison officials so long as the regulations at issue are “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.”

However, two dissenters, Justice John Paul Stevens and Justice Stephen Breyer, noted in their dissents that this ruling could be short-lived if there was another constitutional challenge to the prison’s rules introducing evidence proving that the rules serve no rehabilitative or security purpose.

Stevens said a trial should be held to determine whether Pennsylvania’s goal is legitimate, especially because of the rights at stake: “Plainly, the rule at issue in this case strikes at the core of the First Amendment rights to receive, to read and to think,” Stevens wrote.

–Sergio Munoz-Sarmiento

Comments